Her voice shook with emotion. Her hands went to her face as she spoke.

She said her name, clearly and publicly, at least as a matter of court record. In the filings against Mason Mallon, who was about to be sentenced for sexually assaulting her and another woman on separate occasions, though, she was A.S.

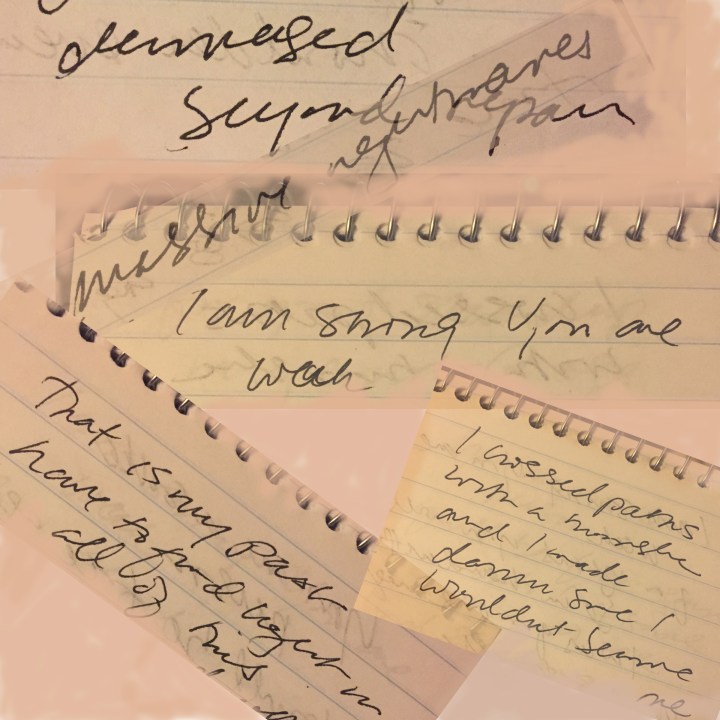

She spoke for several minutes to Mallon, giving a victim impact statement that I later remarked lived up to its name in compelling fashion. She called him a monster, but told him that wasn’t all he was or needed to be. She talked about feeling worthless, “damaged beyond repair,” about suffering through “massive nightmares” and needing medication to sleep.

But she also talked about breaking the cycle of pain he’d inflicted upon her, about how she “crossed paths with a monster” but “made damn sure I didn’t become one.”

“I am strong,” she told him. “You are weak.”

I was a reporter sitting in court for the sentencing, there because this case had a particularly awful novelty: Mallon had posted the aftermath of his violent sexual assault of another woman, identified as K.C. in court, on Snapchat. It was only because an unnamed person saw the photo of the bloodied and unconscious woman online and told police–who found her, still bloody and unconscious, in Mallon’s bedroom–that Mallon was caught.

I didn’t expect either of the victims to be there, let alone to talk. It’s extremely difficult for a person to face another who’s violated them in that way; in fact, the woman on Snapchat was injured so severely she required surgeries to repair the damage he’d inflicted on her body and needed a colostomy bag.

But A.S. was there, a 20-year-old woman confronting the man who’d attacked her when she was just 17 (Mallon was 22 at the time) and telling him–and the court–just how dramatically he’d affected her life.

Mallon rocked back and forth in his chair while she spoke. He smirked at me and at our photographer; he interrupted the judge and accused the lawyer sitting right next to him at the defense table of malpractice. His grandmother was in the courtroom, seated in a wheelchair; his grandfather, also present, asked the attorney to read a statement to the judge saying his grandson had been treated unjustly by the court system.

After the sentencing, I stopped our photographer. I knew he’d taken photos of A.S. but I wasn’t sure he realized the implications of identifying a victim of sexual assault. I told him we needed to ask her permission to publish pictures of her, and she gave it, willingly and explicitly. I asked her for her full name and she gave me that, too, even spelling it for me. I asked if we could publish that, too.

“Yes,” she said right away. “You have my permission.”

I wrestled with that later as I wrote. Certainly she had/has nothing to be ashamed of–nothing that Mallon did to her was her fault. I’ve experienced a sexual assault (though not nearly as traumatic as hers) and I know that it can happen to anyone, no matter how strong, smart, assertive or vigilant they may be–it’s a combination of bad luck and bad people who commit an act based on physical power and violence, not on sex.

But there was something telling me not to use her full name. Maybe it was the old-school journalist in me, the one who follows the rule of not identifying victims of sexual assault. Or maybe it’s that I’m a product of my generation and its mores, and still possessing the instinct that victims of sexual assault need to be not only believed, but also protected.

My editor left it to my discretion, saying it was my byline and so I needed to feel OK with whatever appeared under it.

I called her “A.S.” in the story, though her photograph, with her face in full view, appeared online and in print. I’m not sure if it was because of journalism or because of my conscience, or maybe because I’m almost 48 years old and a mother and I felt like, at 20 years old, she’s still really just a kid. A kid who’s been through a lot, but a kid all the same.

I’m glad I didn’t use her full name. I’ve turned it over and over in my head and, while she was incredibly courageous in coming forward and in confronting her attacker, she also said she did not want this one thing to define her. Her face is out there, but her name is not–not in the newspaper, not on Google, not in an aggregated online crime blotter.

No, this won’t define her at all. Nor should it.